Der Beitrag The Most Common ANSI ASC X12 Parties and How to Use Them erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>If you are not already familiar with X12 file structure and ANSI messaging terminology, you may wish to read our article on the structure of an X12 file before continuing.

If you use EDIFACT instead, read our article on using EDIFACT parties.

What are ANSI X12 parties?

As their name suggests, party identifiers are used in X12 messages to identify certain X12 parties in a particular transaction, such as the shipping party or the receiving party. The party can be an organizational entity, a physical location, property or an individual. The identifiers themselves sit at the start of an N1 segment and are 2-3 characters long.

The full list of X12 party identifiers includes over 1,300 different parties, however most exchanges will only require a few of these. The most commonly used identifiers are listed here:

| ANSI Party Identifier Code | Identifier description |

| N1*BY | Buying Party (Purchaser) |

| N1*SU | Supplier/Manufacturer Party |

| N1*SF | Ship From Party |

| N1*SO | Sold To Party |

| N1*ST | Ship To Party |

| N1*MI | Planning Schedule/Material Release Issuer Party |

| N1*BT | Bill To Party |

For completeness, we have also included the full list of X12 party identifiers at the bottom of this article.

Why is getting X12 party identifiers wrong a common issue?

Within the ANSI ASC X12 standard, there are a multitude of different possible parties that can be involved in a certain transaction. Some of these X12 parties may, in certain cases, be the same as other parties. For example, Bill To and Ship To could easily contain the same information in a particular transaction. Crucially, however, this will not necessarily be true for other transactions.

Unfortunately, confusion over this (or exactly what each party identifier refers to) can lead to poor master data maintenance and incorrect data being exchanged.

Why getting X12 parties right matters

If the correct X12 parties aren’t used, sooner or later errors will occur. These errors can have significant consequences and cost implications. Larger partners, for example, will refuse any invoice that contains data that doesn’t match their records.

Further, correcting master data issues once an issue has been discovered can be time consuming and complicated.

What can I do to avoid using identifiers incorrectly?

In order to avoid future issues, those using X12 parties should…

- Double check the EDI message implementation guideline or “MIG” (and any other relevant documentation) to ensure parties are being used as intended.

- Cross check with other messages in the same chain in case there are interdependencies. For example, an X12 invoice message will usually include the same party identifiers as the preceding order or despatch advice message, but may also include other X12 parties too.

If in doubt, simply check with your partner or EDI service provider. It is always better to ask and get it right first time than to assume.

Want more information?

If you would like more advice on using ANSI ASC X12 parties correctly or streamlining B2B integration more generally, please get in touch. We are always happy to help!

Our resources section also houses a wide selection of articles, webinars, white papers and infographics that you may find useful.

Der Beitrag The Most Common ANSI ASC X12 Parties and How to Use Them erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>Der Beitrag The Structure of an ANSI ASC X12 File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>For more information on using X12 party identifiers correctly, please see our article “The Most Common ANSI ASC X12 Parties and How to Use Them” on this topic.

Segments as basis in the structure of an ANSI X12 file

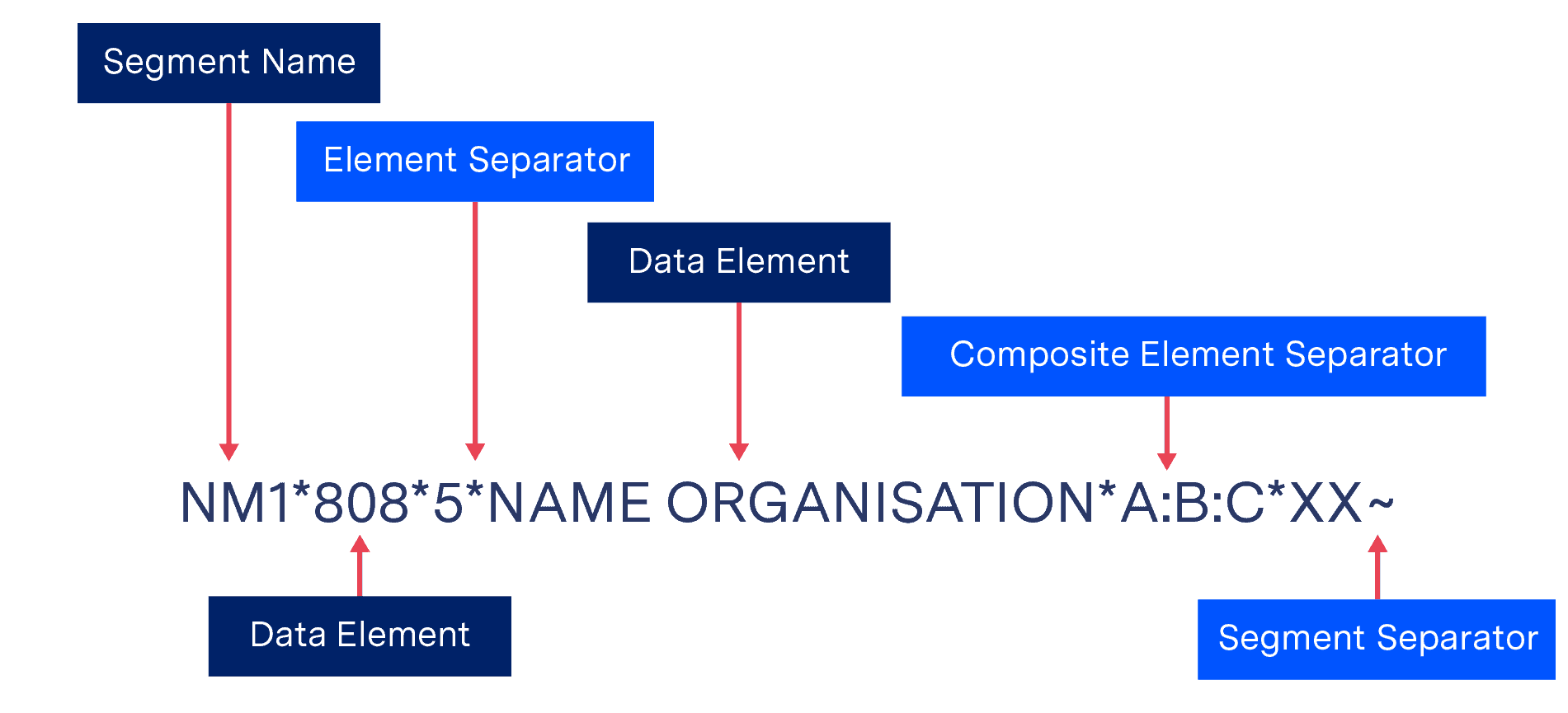

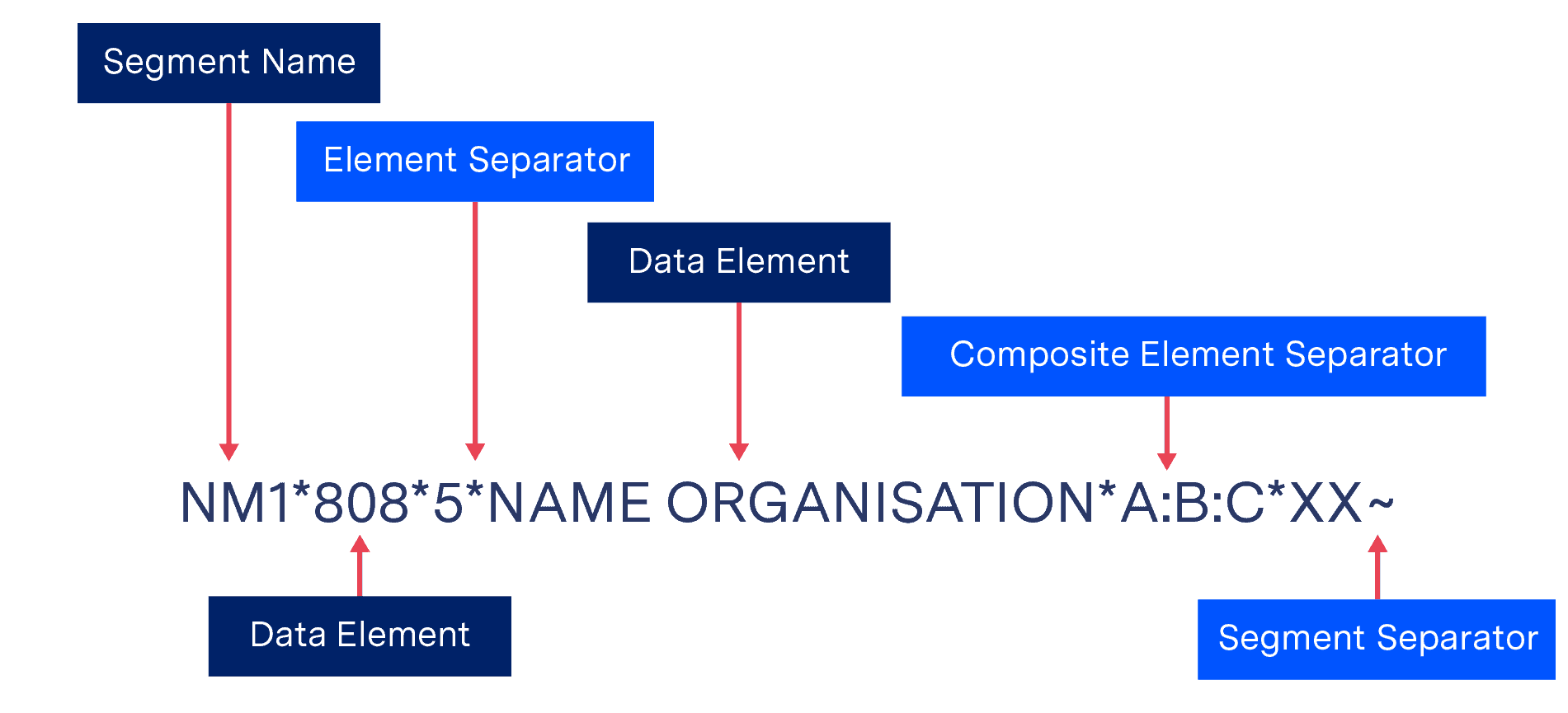

EDI files essentially consist of segments that contain the basic information. Every EDI message is created from these segments, as with ANSI ASC X12. For example, if we simply want to send the name of a partner company, we can use the so-called NM1 segment (easy: NM stands for “name”).

Our example segment could now look like this:

Structure of an ANSI X12 file Example of an ANSI X12 segment

Designations

Segment Name: Stands for the name of the segment. NM1

Element Separator: For separation before data elements. *

Segment Separator: This determines the end of the segment. ~

Data Element: Specified data. 808, 5, NAME ORGANISATION, XX

Composite element: Several data elements can be grouped into a logical unit. A:B:C

Composite Element Separator: Composite elements can be separated. :

The delimiters for the correct reading (“parsing”) of the data or data elements by the EDI solution are element separator, segment separator and composite element separator. Data elements can, for example, simply be text (such as our example company), numbers, time or date specifications, identifiers, etc. Data elements have a certain minimum and maximum length. For example, text is usually longer than a time specification. EDI parsers can also check the permitted length in the structure of the ANSI X12 file.

The ISA segment in the structure of an ANSI X12 file

At the beginning of an EDI file there is the ISA segment, also called Interchange Control Header. The delimiters or separators mentioned above, which the EDI solution uses to divide and read the segment, are determined here and communicated to the EDI solution.

This works because the ISA segment is defined at exactly 106 characters. This means that the EDI solution can search for the character itself at the corresponding position in the segment:

ISA*00* *00* *01*069167604 *ZZ*PLANT-MX *170614*0808*^*00401*000000003*0*T*:~'

Data Element Separator: Character No. 4: *

Repetition Element Separator: (for repeating data elements): Character no. 83: ^ (U would stand for “unused” by the way)

Composite Element Separator: Character Nr. 105: :

Segment Separator: Character Nr. 106: ~

When the structure of an ANSI X12 file becomes more complicated

EDI messages can sometimes become very large. To counteract the complexity, two elements were created for ANSI X12:

Composite Elements

Sometimes a single data element is not specific enough for a message. Then a composite element can be used to help. This is defined in the ISA (Interchange Control Header) segment at the very beginning of a complete EDI message, which we will discuss below. In our case it is :. The EDI solution can then recognize such data elements in the composite and distinguish them by the character.

Recurring elements

With version 5010 X12, repeating data elements (repeating elements) can also be defined. This allows information to be specified more specifically in a segment by using the same data element for more information. This also works with composite data elements. The separator for the EDI solution is again defined in the ISA segment.

For example, we have a CLM segment (CLM stands for “claim”) whose element CLM05 consists of three components: Claim Facility Code Value, Claim Facility Code Qualifier and Claim Frequency Type Code. CLM05 is represented as a composite element with 11:B:1:

CLM*A37YH556*500***11:B:1^12:B:2*Y*A*Y*I*P.

This is now, indicated by ^, cemented with a new composite element 12:B:2.

More questions?

If you have questions about ANSI X12 or EDI more generally, please contact us. We are always happy to help!

More information can also be found on the official ANSI ASC X12 homepage is also worth a click.

Der Beitrag The Structure of an ANSI ASC X12 File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>Der Beitrag The Structure of an ANSI ASC X12 File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>For more information on using X12 party identifiers correctly, please see our article “The Most Common ANSI ASC X12 Parties and How to Use Them” on this topic.

Segments as basis in the structure of an ANSI X12 file

EDI files essentially consist of segments that contain the basic information. Every EDI message is created from these segments, as with ANSI ASC X12. For example, if we simply want to send the name of a partner company, we can use the so-called NM1 segment (easy: NM stands for “name”).

Our example segment could now look like this:

Structure of an ANSI X12 file Example of an ANSI X12 segment

Designations

Segment Name: Stands for the name of the segment. NM1

Element Separator: For separation before data elements. *

Segment Separator: This determines the end of the segment. ~

Data Element: Specified data. 808, 5, NAME ORGANISATION, XX

Composite element: Several data elements can be grouped into a logical unit. A:B:C

Composite Element Separator: Composite elements can be separated. :

The delimiters for the correct reading (“parsing”) of the data or data elements by the EDI solution are element separator, segment separator and composite element separator. Data elements can, for example, simply be text (such as our example company), numbers, time or date specifications, identifiers, etc. Data elements have a certain minimum and maximum length. For example, text is usually longer than a time specification. EDI parsers can also check the permitted length in the structure of the ANSI X12 file.

The ISA segment in the structure of an ANSI X12 file

At the beginning of an EDI file there is the ISA segment, also called Interchange Control Header. The delimiters or separators mentioned above, which the EDI solution uses to divide and read the segment, are determined here and communicated to the EDI solution.

This works because the ISA segment is defined at exactly 106 characters. This means that the EDI solution can search for the character itself at the corresponding position in the segment:

ISA*00* *00* *01*069167604 *ZZ*PLANT-MX *170614*0808*^*00401*000000003*0*T*:~'

Data Element Separator: Character No. 4: *

Repetition Element Separator: (for repeating data elements): Character no. 83: ^ (U would stand for “unused” by the way)

Composite Element Separator: Character Nr. 105: :

Segment Separator: Character Nr. 106: ~

When the structure of an ANSI X12 file becomes more complicated

EDI messages can sometimes become very large. To counteract the complexity, two elements were created for ANSI X12:

Composite Elements

Sometimes a single data element is not specific enough for a message. Then a composite element can be used to help. This is defined in the ISA (Interchange Control Header) segment at the very beginning of a complete EDI message, which we will discuss below. In our case it is :. The EDI solution can then recognize such data elements in the composite and distinguish them by the character.

Recurring elements

With version 5010 X12, repeating data elements (repeating elements) can also be defined. This allows information to be specified more specifically in a segment by using the same data element for more information. This also works with composite data elements. The separator for the EDI solution is again defined in the ISA segment.

For example, we have a CLM segment (CLM stands for “claim”) whose element CLM05 consists of three components: Claim Facility Code Value, Claim Facility Code Qualifier and Claim Frequency Type Code. CLM05 is represented as a composite element with 11:B:1:

CLM*A37YH556*500***11:B:1^12:B:2*Y*A*Y*I*P.

This is now, indicated by ^, cemented with a new composite element 12:B:2.

More questions?

If you have questions about ANSI X12 or EDI more generally, please contact us. We are always happy to help!

More information can also be found on the official ANSI ASC X12 homepage is also worth a click.

Der Beitrag The Structure of an ANSI ASC X12 File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>Der Beitrag EDI file formats explained: key standards and differences erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>- EDI file formats standardise how B2B documents are structured for automated exchange

- Popular formats include EDIFACT, TRADACOMS, X12, VDA, and UBL, each suited to specific industries

- Each format follows different rules, like delimiters or fixed-length fields

- When partners use different formats, conversion is essential and often handled by a managed EDI provider

Document standards are an essential part of electronic data interchange (EDI). In short, EDI standards (aka EDI file formats) are the specific guidelines that govern the content and format of B2B documents such as orders, invoices and order responses. These documents are then sent via EDI protocols to the service provider / business partner.

For more information on ecosio EDI as a Service solution and to find out how we could help your business move to the next step, get in touch today or chat with our Sales team now!

How EDI file formats work

Sending documents according to an EDI standard ensures that the machine receiving the message is able to interpret the information correctly as each data element is in its expected place. Without such standards the receiver’s system will be unable to identify what part of the message is what, making automated data exchange impossible.

Although EDI documents may seem like a random mix of letters and symbols, all EDI messages conform to very strict rules. Typically EDI standards are based on the following four principles:

Syntax

Syntax rules determine what characters can be used and in what order.

Codes

Codes are used to identify common information such as currencies, country names or date formats.

Message designs

The message design defines how a particular message type (e.g. invoice or purchase order) is structured and what subset of rules from the prescribed syntax it uses.

Identification values

The means by which values in an EDI file are identified, e.g. by its position in the file or via the use of separators. These changes from standard to standard.

Most EDI standards also include the following three components:

- Elements – The smallest part of a message, providing submitted values (e.g. “50” or “KGM” or “Potatoes”)

- Segments – A collection of elements or values logically combined to provide an information (e.g. Quantity 50 kilograms of potatoes)

- Transaction sets – A collection of segments, composing a message (e.g. an Invoice for the sale of 50 kilogram of potatoes)

Essentially different formats are like different languages, with the elements and segments of a certain standard mirroring the words and sentences of a regular language.

A brief history of EDI document standards

In the very early days of EDI it quickly became evident that document standards were required to avoid confusion and improve the efficiency of even paper-based supply chain communication. Following the advent of file transfer between computers (FTP) becoming possible, in 1975 the very first EDI standards were published by the Transportation Data Coordinating Committee (an organisation formed by US automotive transport organisations in 1968). In 1981 the American National Standards Institute then published the first multi-industry national standard, X12. In turn this was followed by the creation by the UN of a global standard, EDIFACT, in 1985.

No one attempt to unify standards has ever been completely successful, however. As technology has evolved and industry specific needs have become increasingly disparate, new standards have steadily been introduced over the decades. Somewhat counterintuitively, therefore, today there is no such thing as a single all-encompassing EDI standard for every document type. Instead, businesses choose their preferred document standard from a number of options (usually opting for the one most widely used in their industry). When trading with partners using different standards, businesses then have to ensure that their messages are correctly converted to the recipient’s required format. This process is called mapping.

The 5 most used EDI file format standards:

1) UN/EDIFACT

The most popular EDI file format standard today outside North America is UN/EDIFACT, which stands for United Nations rules for Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce and Transport. These international B2B message guidelines are extremely widely used across many industries.

In fact, given the scope of EDIFACT’s adoption, several industries have developed subsets of the main standard which allow for automation of industry-specific information. One well-known subset is EANCOM, for example, which is used in the retail industry.

EDIFACT document file types are identified by a six letter reference. For example, three of the most common of these references are:

- ORDERS (for purchase orders)

- INVOIC (for invoices)

- DESADV (for despatch advice)

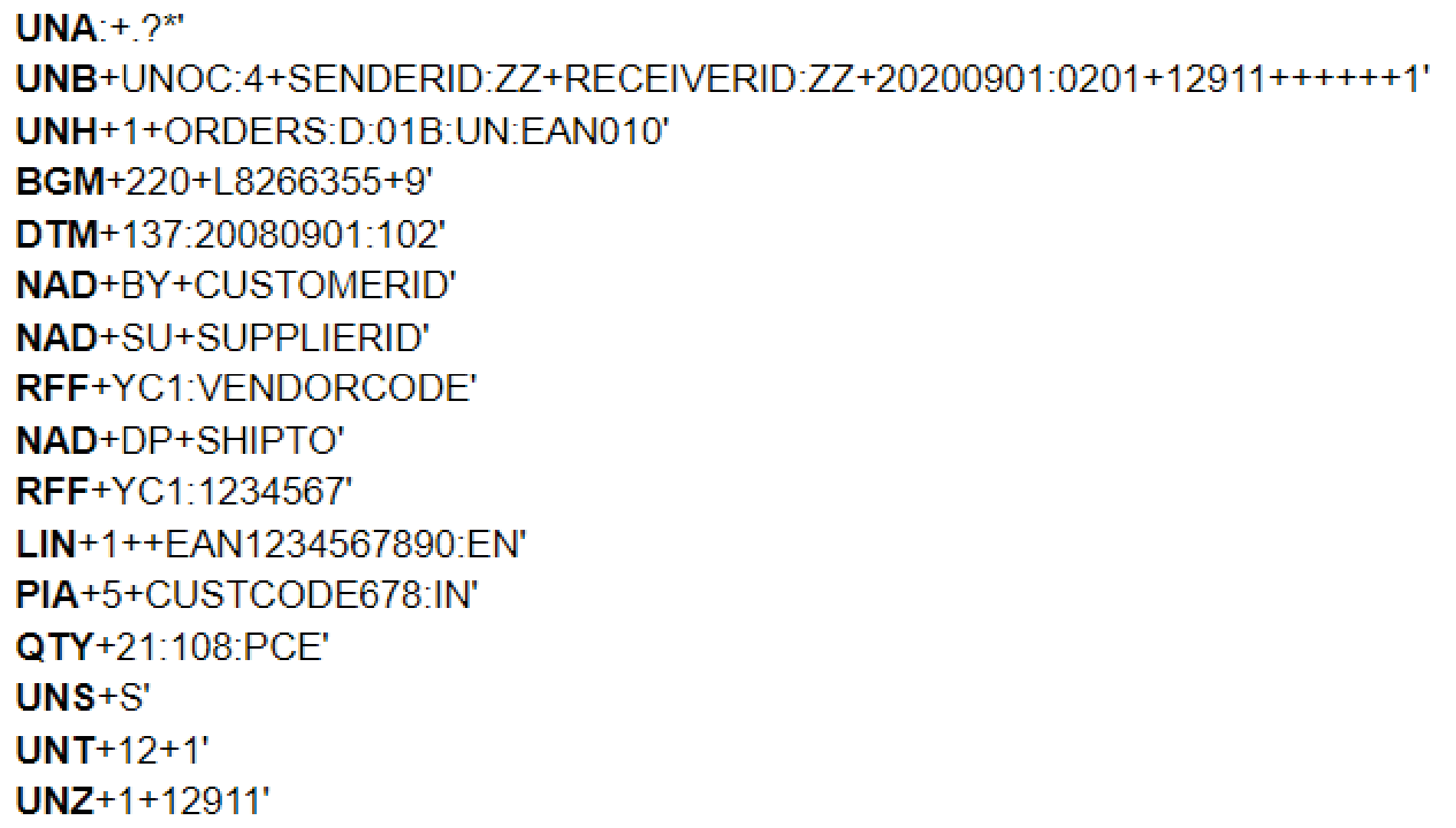

All of these EDIFACT messages have the same basic structure, consisting of a sequence of segments:

- UNA – separators, delimiters and special characters are defined for the interpreting software

- UNB – file header (with the file end UNZ this makes up the envelope, containing basic information)

- UNG – group start

- UNH – message header

- UNT – message end

- UNE – group end

- UNZ – file end

Example EDIFACT order

As well as transmission format, the EDIFACT standard also defines delivery requirements. EDIFACT provides set guidelines, for example, concerning the exact structure of specific message exchanges, which might themselves contain several individual EDIFACT files.

For a more detailed look at the structure of an EDIFACT file, see our blog post “EDI Standards Overview – Structure of an EDIFACT File” on this topic.

2) TRADACOMS

Despite being less widely-used than EDIFACT, the TRADACOMS standard was released several years before the UN standard. Designed primarily for UK domestic trade (and particularly popular in the retail industry), TRADACOMS is made up of a hierarchy of 26 messages. Like EDIFACT, each message is also given a six letter reference.

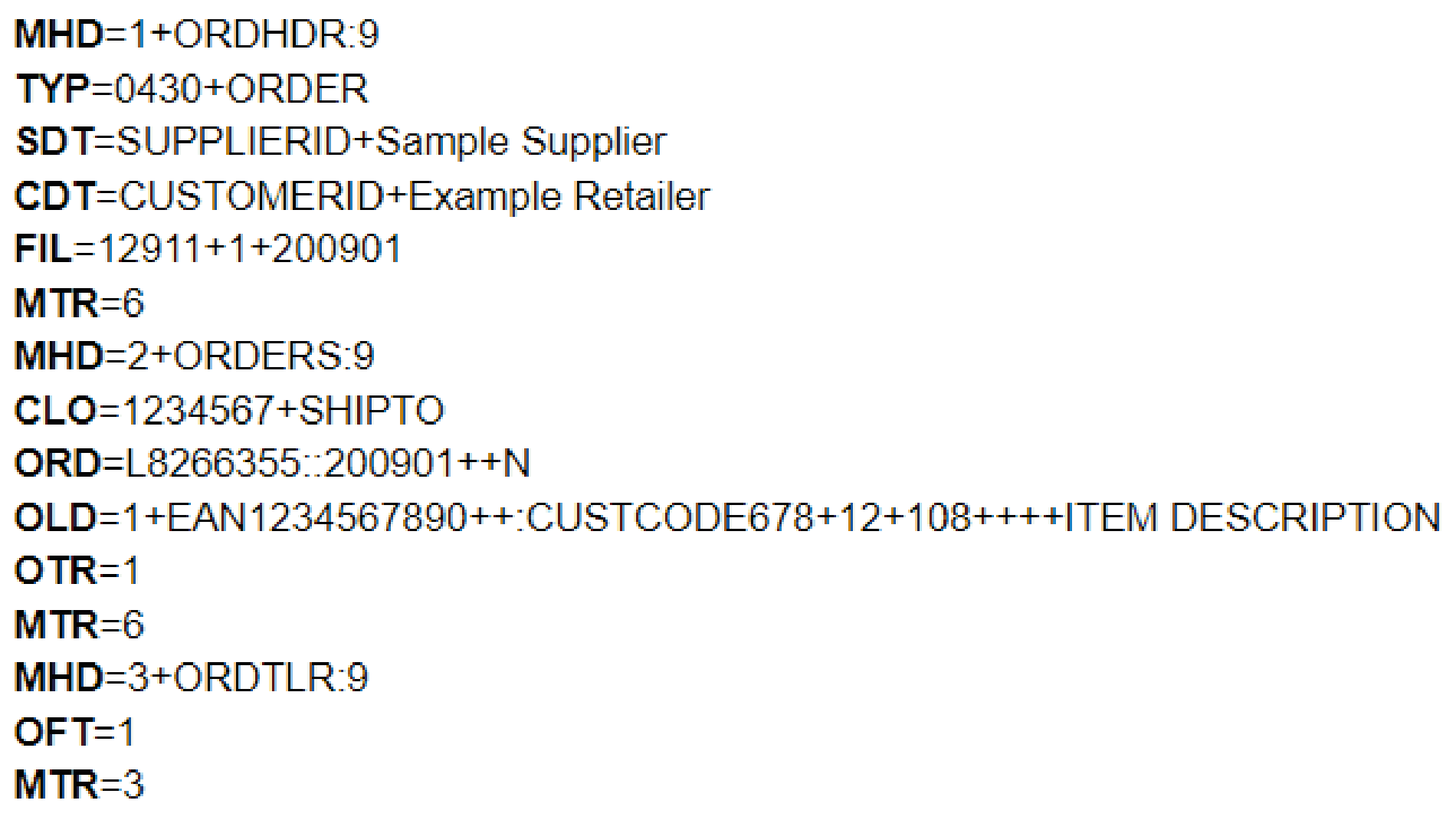

TRADACOMS does not use a single message format. Instead, a transmission to a trading partner will consist of a number of messages. For example, one purchase order will often contain an Order Header (ORDHDR), several Orders (ORDERS) and an Order Trailer (ORDTLR). Multiple individual order messages can repeat between the ORDHDR and the ORDTLR.

As with EDIFACT standards, the TRADACOMS standard uses segments for ease of translation. Below are four of the most common segments:

- STX – Start of Interchange

- MHD – Message start

- MTR – Message end

- END – End of Interchange

Example TRADACOMS order

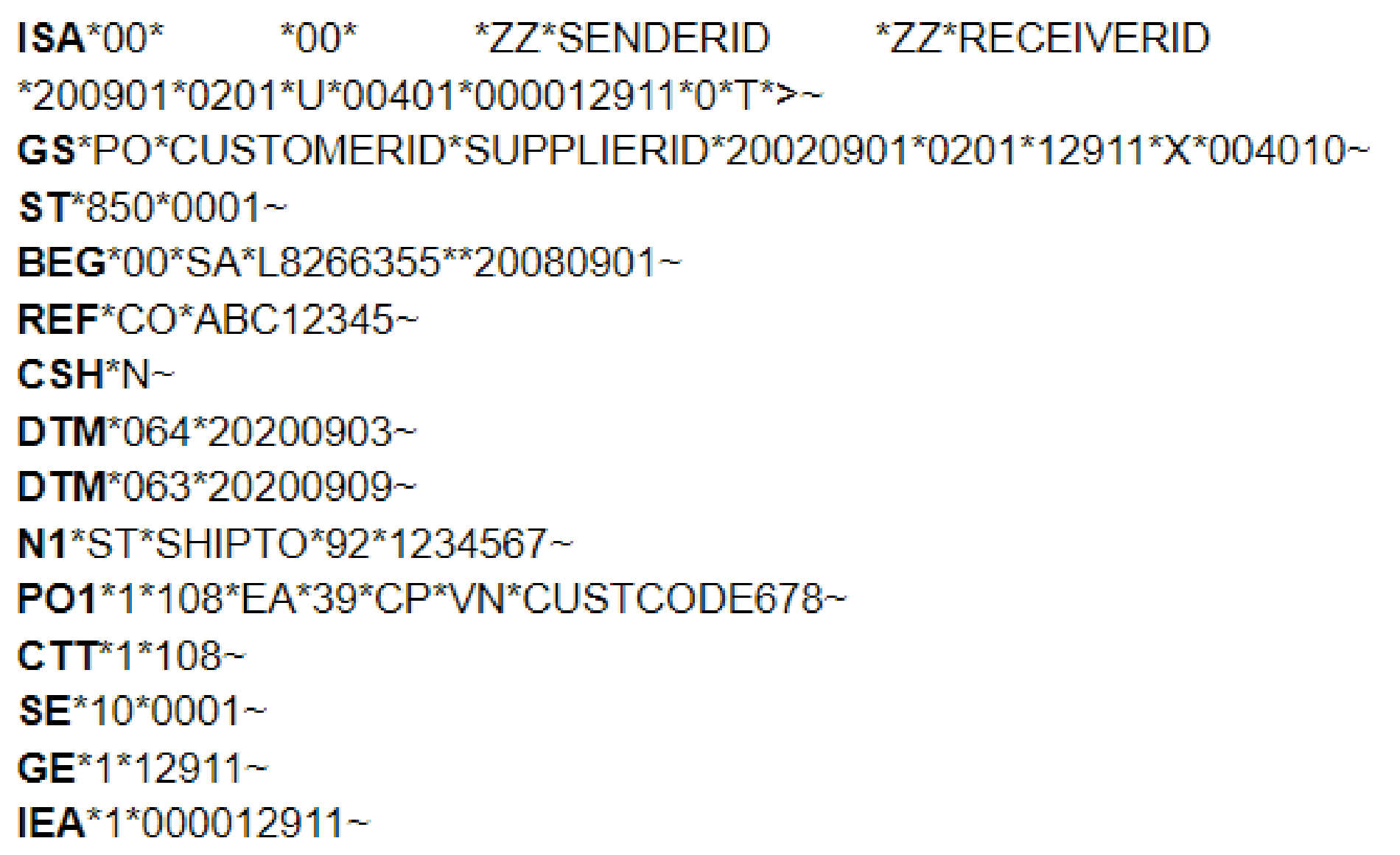

3) ANSI ASC X12

ANSI ASC X12 stands for American National Standards (ANSI) Accredited Standards Committee (ASC) X12, though (for obvious reasons) this is often abbreviated to just X12.

Though initially developed in 1979 to help achieve EDI document standardisation across North America, X12 has been adopted as the preferred standard by approaching half a million businesses worldwide.

Compared to other EDI standards organisations, X12 has a particularly comprehensive transaction set. There are over 300 X12 standards, all of which are identified by a three digit number (e.g. 810 for invoices) rather than the six letter code system used by EDIFACT and TRADACOMS. These EDI file format standards fall under X12’s different industry-based subsets:

- AIAG – Automotive Industry Action Group

- CIDX – Chemical Industry Data Exchange

- EIDX – Electronics Industry Data Exchange Group (CompTIA)

- HIPAA – Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- PIDX – American Petroleum Institute

- UCS – Uniform Communication Standard

- VICS – Voluntary Interindustry Commerce Standards

With each containing slight variations, these subsets are used by different industries as appropriate (apparel retail businesses use VICS for example).

In addition, the hundreds of document types are divided into 16 helpful message series, from ‘order’ to ‘transportation’, with each containing the relevant individual message types.

As with Documents conforming to X12 standards are made up of several segments, some of which are optional and some mandatory. Below is a list of the mandatory segments:

- ISA – Start of interchange

- GS – Start of functional group

- ST – Start of transaction set

- SE – End of transaction set

- GE – End of functional group

- IEA – End of Interchange

As with all EDI documents, these segments in turn are comprised of elements, as can be seen in the example X12 document below:

Example X12 order

For more information on the X12 format, please see our more recent article “EDI Standards Overview – Structure of an EDIFACT File”.

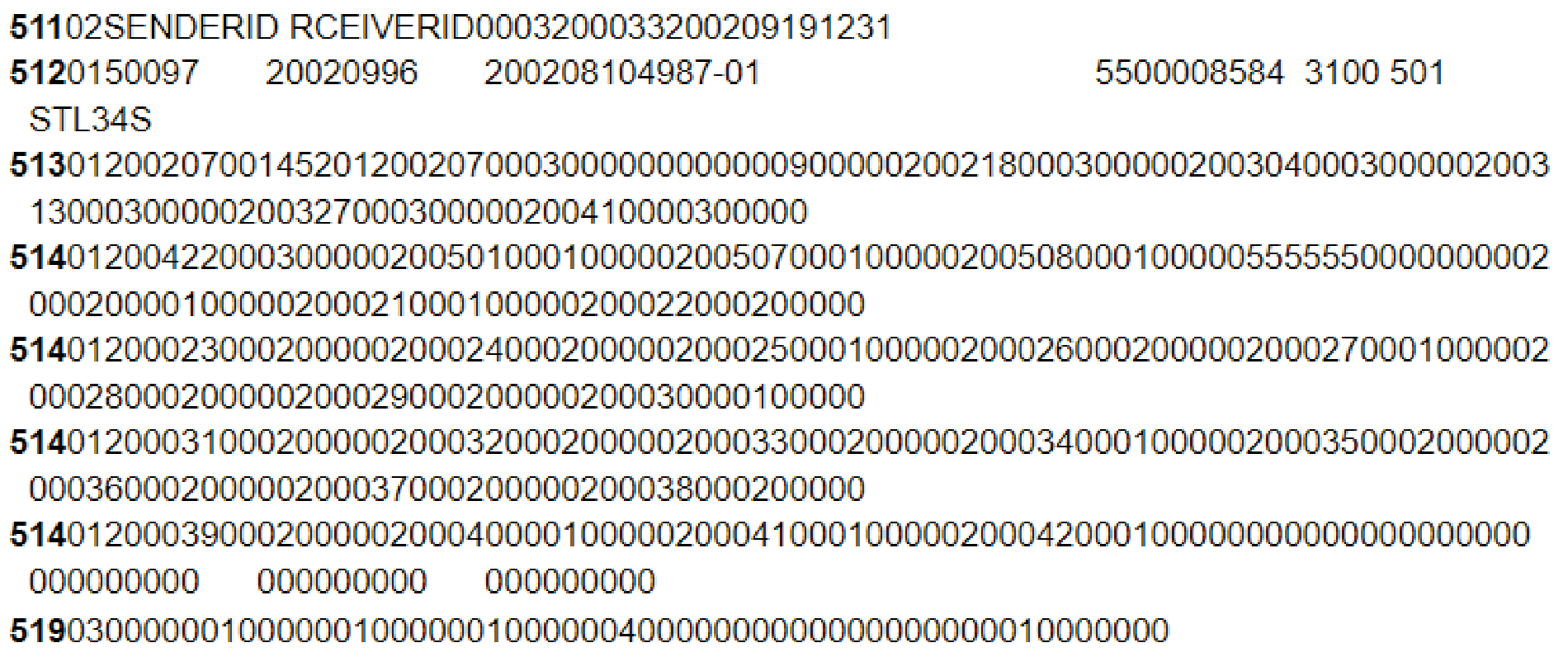

4) VDA

The Association of the Automotive Industry (Verband der Deutschen Automobilindustrie in German, or VDA for short) was established in 1901 by German automobile businesses.

The VDA was one of the first associations to develop EDI file formats in 1977, making VDA standards even older than EDIFACT.

Like X12 standards, every VDA message standard has a unique identification number (four digits long in this case). For example, VDA EDI file format 4905 is a delivery forecast.

As worldwide use was not expected when the standards were developed, all VDA standards were published in German – something that continues to this day. This can make interpretation difficult, particularly concerning German business terms. Likewise, as VDA also does not use a naming convention for each element, knowledge of German is required to identify them.

Unlike EDIFACT and X12 standards, VDA standards do not use segments or separators. Instead data elements with a constant length, known as fixed length format elements, are used. When the data to be transmitted is shorter than the required length, spaces are used to fill the gaps. Unfortunately, this fixed length format means that the amount of data that can be transmitted is limited, meaning conversion to/from other EDI standards can be difficult.

Because of these issues, VDA fixed length document standards are slowly being replaced by EDIFACT document types. Today, VDA standards are effectively a subset of the EDIFACT standards used extensively by the automotive industry (much like the EDIFACT subset CEFACT is used by retail businesses).

To aid those using their standards, the VDA have published suggestions regarding transition to EDIFACT.

Example VDA delivery forecast

For more information on VDA standards, please see our dedicated VDA blog post for a more comprehensive explanation.

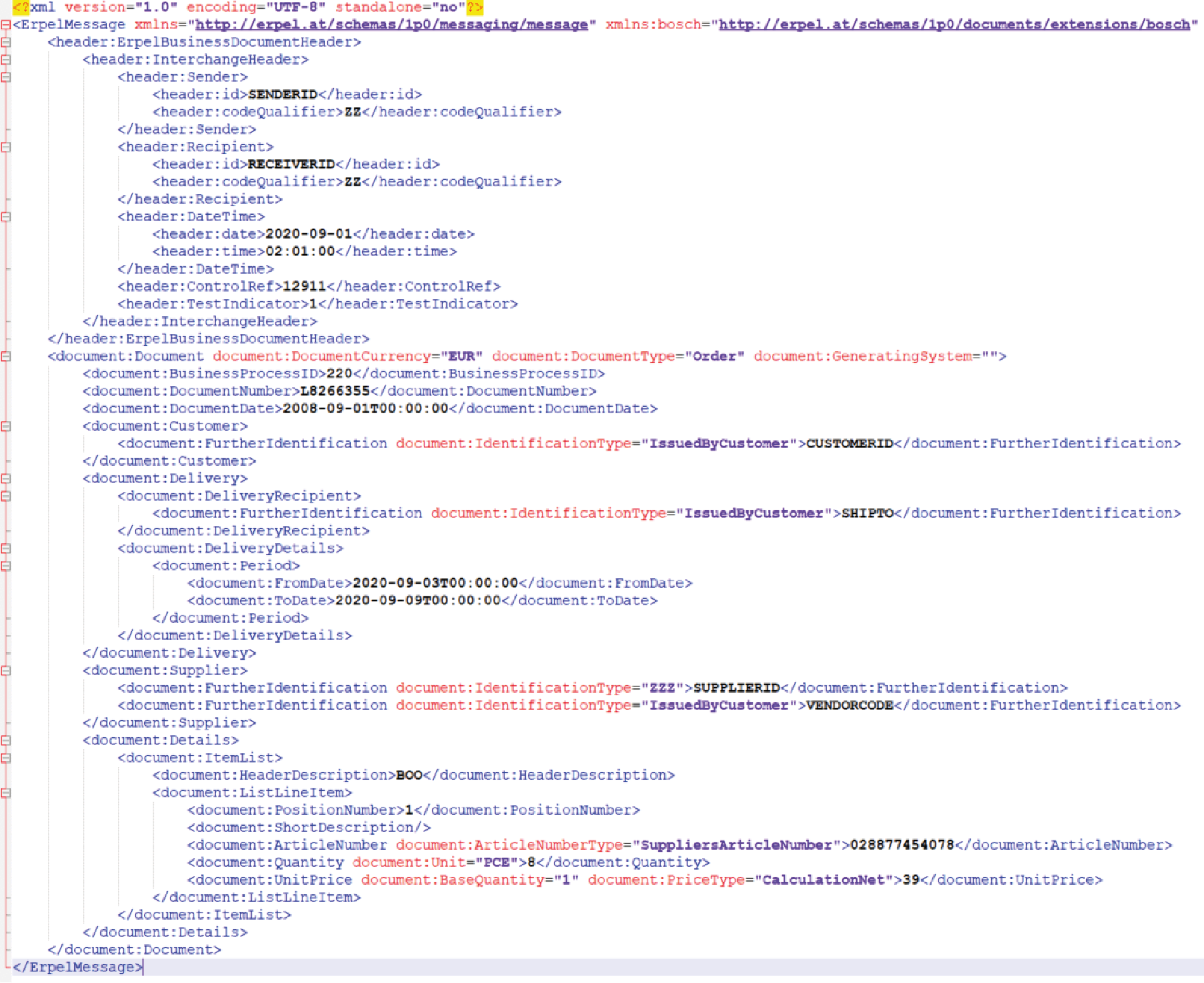

5) UBL

The Universal Business Language, or UBL, is a library of standard XML-based business document formats. UBL is owned by Organisation for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS), who have made it available to all businesses for free.

As UBL uses an XML structure it differs from other more traditional EDI document formats. Perhaps the biggest difference is the fact that XML-based transmissions are easier to read than other EDI file formats. However, XML file sizes are considerably larger than those of other EDI file formats, though this is no longer a problem following the advent of broadband internet.

When first established in 2003, UBL had seven EDI file format standards. By the time version 2.1 was released over a decade later this number had increased to 65, and the release of version 2.2 in 2018 further increased the number of document types to over 80.

Significantly CEN/TC434 recently named UBL as one of two EDI syntaxes which comply with new EU regulations regarding e-invoicing. As such, as the use of PEPPOL grows, so the use of UBL is also likely to increase.

Like X12, UBL message types are split into higher level categories. These categories include pre-award sourcing, post-award sourcing, procurement and transportation. UBL messages themselves, meanwhile, include validators, generators, parsers and authoring software.

Example XML order (ecosio ERPEL)

How to exchange different EDI file formats with your trading partners

Whilst each of the above document standards is widely used, particularly within certain industries, unfortunately no one set of document standards is universally used by all supply chain businesses. As a result, if you wish to grow your business and to automate B2B data exchange with your partner network to achieve the cost benefits of automation you will need the ability to translate data between numerous formats.

Given the amount of technical expertise EDI file format translation requires, the fastest and most efficient way to gain this capability is to enlist the help of a managed EDI solution provider such as ecosio. In addition to enabling you to transfer documents in any required format and over any EDI protocol via a single connection to the ecosio cloud-based EDI solution (our Integration Hub), ecosio’s managed services remove virtually all internal effort concerning EDI. For example, new onboardings are handled by a dedicated project manager who is experienced in liaising between both sides to achieve fast, hassle-free and successful connections. Similarly, ecosio’s unique API ensures users are able to send and receive data directly from their ERP’s existing user interface.

For more information on ecosio EDI as a Service solution and to find out how we could help your business move to the next step, get in touch today or chat with our Sales team now!

Der Beitrag EDI file formats explained: key standards and differences erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>Der Beitrag EDI Standards Overview – Structure of an EDIFACT File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>- EDIFACT files are structured by a clear schema, governed by an EDI standard that defines syntax rules, code usage, message layouts and value identification methods

- Syntax rules specify which characters are allowed and in what sequence, ensuring the file can be processed by computer systems

- Message design dictates the hierarchy of message types, such as invoices or delivery notes, and guides how these are composed within the file

- Value identification relies on separators rather than positional metadata, meaning EDIFACT uses explicit delimiters to parse information, unlike CSV or flat files

EDI standards

An EDI file may seem like a random jumble of characters at first glance. On closer examination, however, a well-thought-out schematic structure is revealed, which makes the processing of the message by computer programs possible in the first place. Behind an EDI file is a specific EDI standard that dictates how the file must be structured. Typical standard formats that can be used here are, for example, EDIFACT, XML, CSV files or flat file formats.

An EDI standard usually builds on the following four principles:

Syntax rules

The syntax rules define the allowed characters and the allowed order in which the individual characters may be used.

Codes

Within an EDI file most of the information is accurately identified using codes – for example, currency codes, country codes, but also codes for identifying a particular date format, etc.

Message design

The message design defines the structure of a particular message type. Message types include, for example, purchase orders, delivery notes, invoices, etc.

Identification of values in an EDI message

Depending on the standard used, there are three ways in which a value can be identified in an EDI file:

a) Implicitly by the position in the message. This technique is used in flat file formats and CSV. The exact position and semantic of a given value is defined in the accompanying documentation. For example: A line beginning with the characters 100 stands for the header line. The characters from position 4 – 17 in a line beginning with 100 represent the GLN of the sender, etc.

b) Implicitly through the use of separators. Using a set of predefined separator characters, a message structure is explicitly defined. The message structure defines which building blocks are to be used and in which order the building blocks must be aligned to form a correct EDI message, e.g., an orders message. This technique is used in EDIFACT files.

c) Explicitly through the application of metadata. With the help of additional data, the meaning of the individual information fragments in a file is specified more precisely. This technique is used in XML, for example, where the actual information is enclosed by means of markup elements and attributes – e.g.:

<InvoiceRecipient id="IV4394">Recipient of invoice</InvoiceRecipient>

UN/EDIFACT – A standard of the United Nations

UN/EDIFACT is the abbreviation for United Nations Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce, and Transport. The standardization organization behind UN/EDIFACT is UN/CEFACT (United Nations Center for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business). UN/EDIFACT is one of the most widely used EDI standards today alongside ANSI ASC X12. ANSI ASC X12 is very common in the North American market, whereas in Europe UN/EDIFACT prevails (or one of the various subdialects).

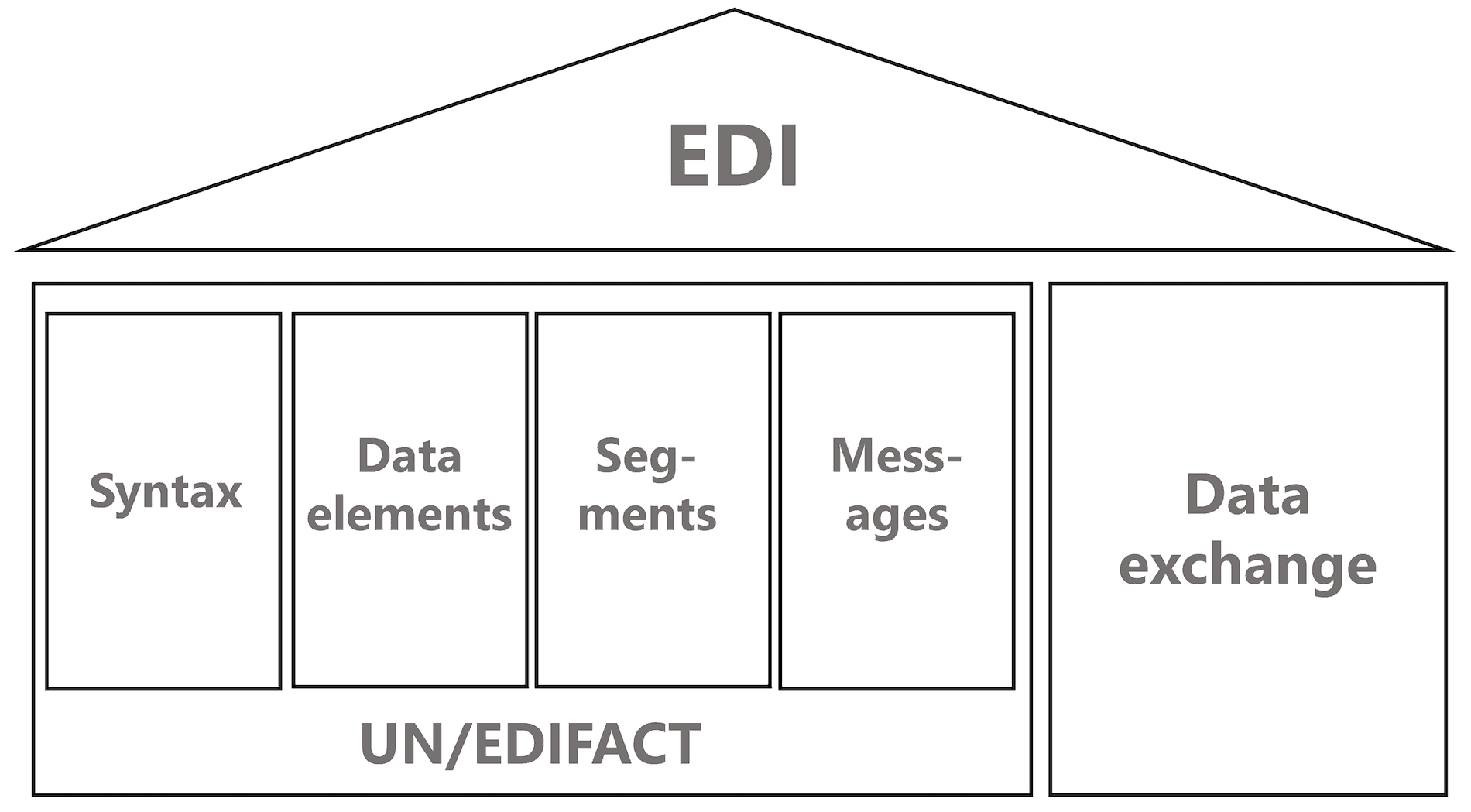

As the following figure shows, the UN/EDIFACT standard is based on four different pillars.

Syntax

The syntax defines the exact rules for message building, as well as the characters used to separate individual message segments and elements.

Data elements

A data element is the smallest unit in an EDIFACT file.

Segments

Groups of similar data elements form so-called segments.

Messages

Messages represent an ordered sequence of segments – for example, a DESADV file represents a delivery note.

Additionally, the EDIFACT standard defines message delivery requirements. For example, the exact structure of a specific message exchange, which in turn may contain several EDIFACT files.

EDIFACT standards

The exact structure of an EDIFACT message is defined in official standard documents, which are also available online. UN/CEFACT approves two EDIFACT standard versions per year, each marked with the year followed by “A” (for the first release of a year) and “B” (for the second release of a year). D01B is therefore the second standard version from the year 2001.

In addition, separate subsets of the official UN/EDIFACT standard exist for the various industry sectors and domains. In the consumer goods sector the EANCOM subset is very common, which is also used for the example of this article. EANCOM is the world’s most widely used standard for electronic data interchange. The most frequently used EANCOM message types are ORDERS, DESADV and INVOIC.

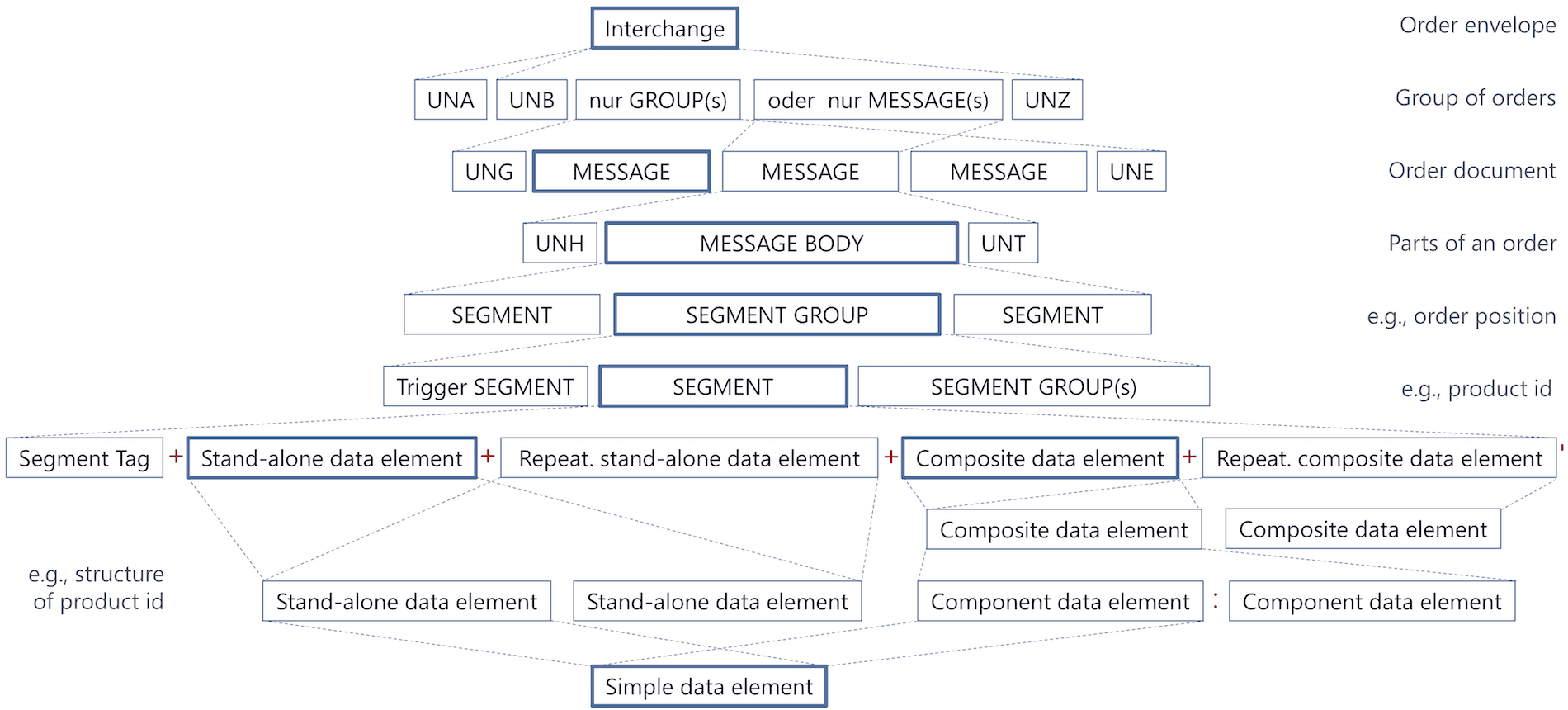

Structure of an EDIFACT file

An EDIFACT file follows an exact hierarchy, which is denoted below.

The topmost unit of an EDIFACT message is the Interchange (UNB), which can be thought of as an envelope. The interchange defines the message recipient, the message sender, the message number, the message date, etc.

An interchange can in turn contain several individual Groups (UNG) representing message groups. Alternatively, an interchange can also contain individual messages (concrete messages). Mixing of individual messages and message groups within an interchange is not allowed.

A message itself is enclosed by a header (UNH) and a trailer segment (UNT). A message group is surrounded by an UNG and UNE segment.

Within a message, there are several segments and segment groups, which represent individual related message parts (for example, information about the biller, a specific invoice line, etc.). A segment group is initiated by a so-called trigger element.

Segments consist of data elements and composite data elements.

The smallest unit of an EDIFACT file are simple data elements.

Simple Data Elements

Simple data elements form the basic building blocks of an EDIFACT file and represent – as the name already suggests – simple data values.

An example for a simple data element is a party name.

3036 – Party Name

Description: Name of a party.

Representation: an..35

Example:

John Doe

The abbreviation an..35 means, that a maximum of 35 alphanumeric characters may be used for the party name.

Simple data element with code list

For a simple data element with code list no free text can be used, but a list of predefined values (= codes) must be used.

An example for a simple data element with code list is a coded document name.

1001 Document name code

Description: Code specifying the document name.

Representation: an..3

Example:

1 Certificate of analysis

Certificate providing the values of an analysis.

2 Certificate of conformity

Certificate certifying the conformity to predefined

definitions.

3 Certificate of quality

Certificate certifying the quality of goods, services

etc.

4 Test report

Report providing the results of a test session.

…

Composite Data Element

A composite data element consists of individual simple data elements and represents data with additional metadata (= additional data describing the actual data).

The individual components within a composite data element (typically simple data elements and simple data elements with code lists) are separated using the : character.

An example for a composite data element is a duty/tax or fee type.

C241 – DUTY/TAX/FEE Type

Structure:

| 5153 | Duty or tax or fee type name code | C | an..3 |

| 1131 | Code list identification code | C | n..17 |

| 3055 | Code list responsible agency code | C | an..3 |

| 5152 | Duty or tax or fee type name | C | an..35 |

Example:

The following example shows an exemplary duty/tax/fee type.

AAA:52:1:tax type xyz

AAA = Petroleum tax

52 = Value added tax identification

1 = CCC (Customs Co-operation Council)

tax type xyz = Free text description of tax

Segments

Segments consist of simple data elements and composite data elements and represent compound data, such as an address.

The individual data elements in a segment are separated by the + character. A segment starts with the three-digit segment identifier and ends with the ' character.

The exact structure of a segment is described by means of so-called segment tables. The following segment table describes the structure of the LIN (line item) segment segment .

010 1082 LINE ITEM IDENTIFIER C 1 an..6

020 1229 ACTION REQUEST/NOTIFICATION DESCRIPTION

CODE C 1 an..3

030 C212 ITEM NUMBER IDENTIFICATION C 1

7140 Item identifier C an..35

7143 Item type identification code C an..3

1131 Code list identification code C an..17

3055 Code list responsible agency code C an..3

040 C829 SUB-LINE INFORMATION C 1

5495 Sub-line indicator code C an..3

1082 Line item identifier C an..6

050 1222 CONFIGURATION LEVEL NUMBER C 1 n..2

060 7083 CONFIGURATION OPERATION CODE C 1 an..3

M indicates “mandatory”, i.e., the simple data element or composite data element must be specified. C stands for “conditional” and means that the data element can optionally be specified. The values an..3, an..17, etc. represent the number of permitted alphanumeric characters.

Assume we want to represent the following line item information using the LIN segment.

Pineapples

Line item number: 2

GTIN: 9393398439325

Type: article has been added

The resulting EDIFACT segment is:

LIN+2+1+9393398439325:EN'

Segment groups

Segment groups are used to aggregate several individual segments into groups of related segments.

For example, the following segment group allows to specify contact details by combining the segments CTA (Contact information) and COM (Communication contact).

0220 ----- Segment group 5 ------------------ C 5----------+| 0230 CTA Contact information M 1 || 0240 COM Communication contact C 5----------++

Some possible segment sequences would be for example:

CTA-CTA-CTA-COM-COM-CTA-COM CTA CTA-COM-CTA-CTA ...

As indicated by C 5, the segment group itself is optional and may occur up to 5 times. The segment group is initiated by a so-called trigger segment. It is the first element within the segment group that usually has cardinality M 1 (that is, it must occur exactly once).

Please see our article for more on the EDIFACT PRI segment.

Messages

A message represents a related sequence of segments and represents a concrete business document – for example, an DESADV message (dispatch advice). The following section shows the first part of a DESADV definition.

0010 UNH Message header M 1

0020 BGM Beginning of message M 1

0030 DTM Date/time/period C 10

0040 ALI Additional information C 5

0050 MEA Measurements C 5

0060 MOA Monetary amount C 5

0070 CUX Currencies C 9

0080 ----- Segment group 1 ------------------ C 10----------+

0090 RFF Reference M 1 |

0100 DTM Date/time/period C 1-----------+

0110 ----- Segment group 2 ------------------ C 99----------+

0120 NAD Name and address M 1 |

0130 LOC Place/location identification C 10 |

|

0140 ----- Segment group 3 ------------------ C 10---------+|

0150 RFF Reference M 1 ||

0160 DTM Date/time/period C 1----------+|

|

0170 ----- Segment group 4 ------------------ C 10---------+|

0180 CTA Contact information M 1 ||

0190 COM Communication contact C 5----------++

0200 ----- Segment group 5 ------------------ C 10----------+

0210 TOD Terms of delivery or transport M 1 |

0220 LOC Place/location identification C 5 |

0230 FTX Free text C 5-----------+

...

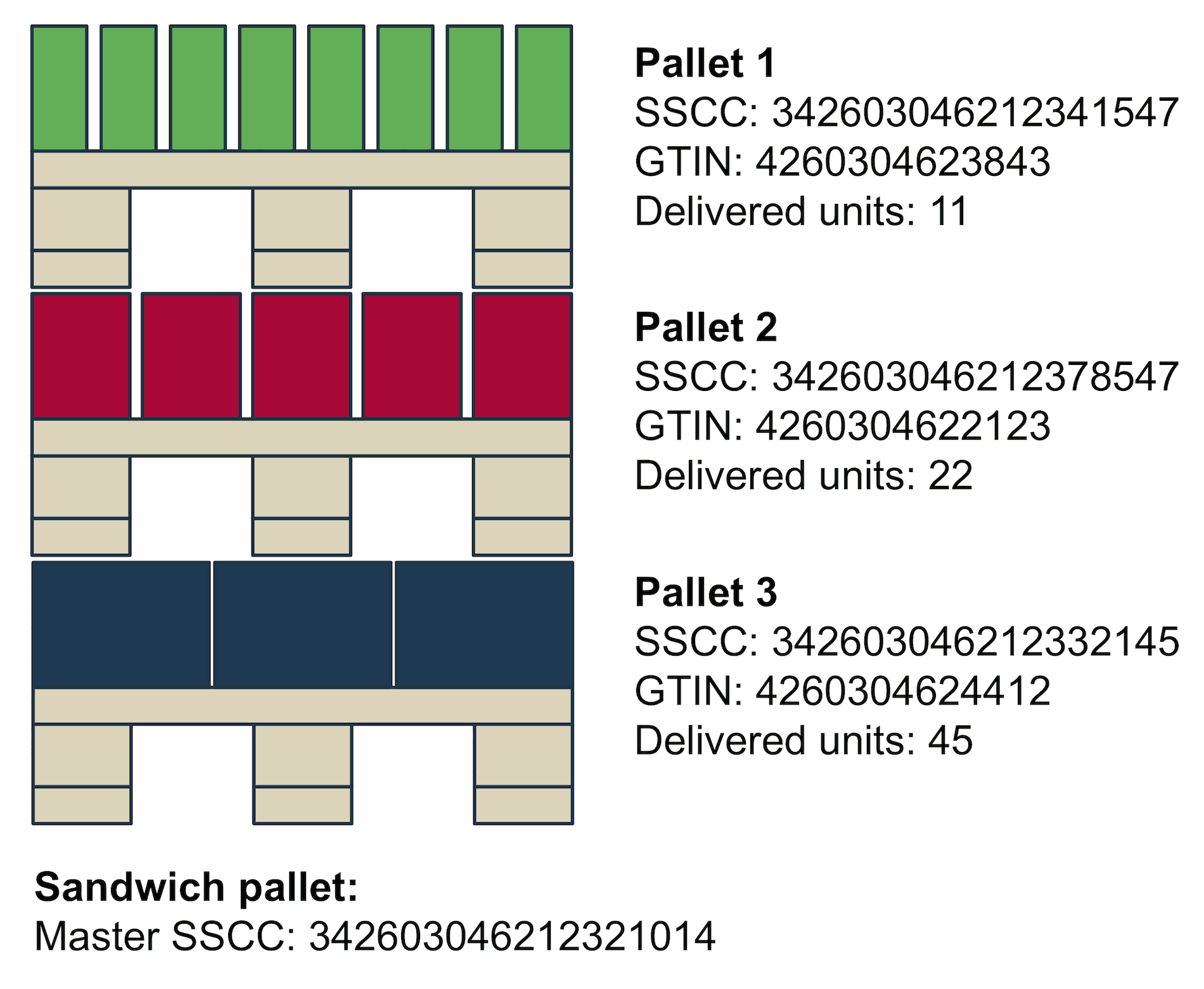

EDIFACT sample dispatch advice

In the following EDIFACT dispatch advice example we will represent the delivery structure shown in the figure below.

Based on the previous concepts, the example now shows a concrete EDIFACT message for a dispatch advice. To increase readability, line breaks have been added after each segment. In a regular EDIFACT file no line breaks shall be used.

UNA:+.? ' UNB+UNOA:3+8773456789012:14+9123456789012:14+140218:1552+MSGNR4711++++++1' UNH+1+DESADV:D:96A:UN:EAN005' BGM+351+DOCNR4712+9' DTM+137:20180218:102' DTM+2:20180220:102' NAD+SU+9983083940382::9' NAD+BY+5332357469542::9' NAD+DP+3839204835454::9' CPS+1' PAC+1++PK' PCI+33E' GIN+BJ+342603046212321014' CPS+2+1' PAC+11++CT' PCI+33E' GIN+BJ+342603046212341547' LIN+1++4260304623843:EN' QTY+12:110:PCE' RFF+ON:8493848394:1' CPS+3+1' PAC+22++CT' PCI+33E' GIN+BJ+342603046212378547' LIN+2++4260304622123:EN' QTY+12:330:PCE' RFF+ON:8493848394:2' CPS+4+1' PAC+45++CT' PCI+33E' GIN+BJ+342603046212332145' LIN+3++4260304624412:EN' QTY+12:450:PCE' RFF+ON:8493848394:3' CNT+2:3' UNT+34+1' UNZ+1+MSGNR4711'

In the following, we examine the structure of the individual segments in detail.

UNA segment

UNA:+.? '

The UNA segment stands for the “Service String Advice” and describes the separators used in the message. Usually, the following separators are used (syntax version 3).

: Composite element delimiter

+ Data element delimiter

. Character reserved for the decimal comma

? release character (escape character)

remains empty

' Segment delimiter

UNB segment

UNB+UNOA:3+8773456789012:14+9123456789012:14+140218:1552+MSGNR4711++++++1'

The UNB segment represents the interchange header, and contains information about the message sender, the message recipient, the message date, and so on.

UNOA stands, for example, for the character set used. Examples for permitted character sets are:

UNOA = UN/ECE level A; complies with ISO 646 – also called International Alphabet No. 5 – except lowercase letters.

UNOB = UN/ECE level B; like UNOA but also lowercase letters.

UNOC = UN/ECE level C; complies with ISO8859-1

UNOD = UN/ECE level D; complies with ISO8859-2

UNOE = UN/ECE level E (Cyrillic)

UNOF = UN/ECE level F (Greek)

3 identifies the UN/EDIFACT syntax version. There are four different UN/EDIFACT syntax versions. Nowadays mostly syntax version 3 and 4 are used.

8773456789012:14 corresponds to the sender of the message.

9123456789012:14 corresponds to the recipient of the message.

The identifier 14 indicates that the number is a GLN.

140218:1552 stands for February 18, 2014, 15:52.

MSGNR4711 is the unique number of the interchange. It is used in particular in the context of message routing for the unique identification of a message transmission.

The last 1 indicates that the test indicator is set and that the given interchange is a test message. This information is also important for message routing, because the recipient can distinguish production messages from test messages and they can be processed accordingly different.

UNH segment

UNH+1+DESADV:D:96A:UN:EAN005'

The UNH segment represents the header of a document. The number 1 is the unique number of the document within the interchange. The number is assigned by the sender.

DESADV:D:96A:UN indicates that the document is a dispatch advice and that the document type is from UN/EDIFACT Directory D96A. EAN005 indicates that it is an EANCOM document type and identifies the EANCOM version of the D96A EANCOM standard used.

BGM segment

BGM+351+DOCNR4712+9'

The BGM (beginning of message) segment initiates the actual document.

351 corresponds to the concrete document subtype. Examples for permitted values are:

351 = Despatch advice

35E = Returns advice (EAN Code)

YA5 = Cross dock despatch advice (EAN Code)

DOCNR4712 is the unique number of the document given by the sender.

DTM segment

DTM+137:20180218:102' DTM+2:20180220:102'

The DTM segment is used to specify date and time information.

The first part of this composite data element identifies the type of the date (date/time/period qualifier). For example:

137 = Document/message date/time. Date/time when a document/message has been issued.

2 = Delivery date/time, requested date on which buyer requests goods to be delivered

The second part represents the actual date value:

20180218 for example, February 18, 2018.

The third part specifies the pattern for the date (date/time/period format qualifier).

102 corresponds to CCYYMMDD

NAD segment

NAD+SU+9983083940382::9' NAD+BY+5332357469542::9' NAD+DP+3839204835454::9'

The NAD segment is used to indicate the names and addresses of the companies involved. Instead of names and addresses, however, in most cases the unique identification by means of numbers, such as the GLN (global location number), is used.

The first part of the composite data element identifies the concrete type of business partner (party qualifier). Examples for permitted values are:

BY = Buyer

DP = Delivery party

SU = Supplier

WH = Warehouse keeper

The second part represents the 13-digit GLN and 9 indicates, that the provided number is a GLN number.

CPS segment

CPS+1'

A dispatch advice is structured using the concept of consignment packing sequences. Thereby, a CPS represents a specific layer in the hierarchy of a shipment, e.g., a pallet, a box, a carton, etc.

The number 1 indicates the hierarchy level, which in this case is level 1. Further CPS sequences may then refer to the upper layer, using the second digit. For example:

CPS+2+1'

indicates consignment packing sequence 2. The parent layer is consignment packing sequence 1.

PAC segment

PAC+1++PK'

The PAC segment is used to specify the number and the type of packages. In the example above 1 packaging of type PK (package) is denoted. Other packaging types are for instance:

09 = Returnable pallet (EAN Code)

201 = Pallet ISO 1 – 1/1 EURO Pallet (EAN Code)

PK = Package

SL = Slipsheet

PCI segment

PCI+33E'

The PCI segment is used to specify markings, which are used to uniquely identify the packages in the shipment. In retail mostly SSCC (serial shipping container codes) are used.

The code 33E indicates: marked with serial shipping container code.

GIN segment

GIN+BJ+342603046212321014'

GIN stands for goods identify number and is used to specify the code, which is attached to the packaging.

LIN segment

LIN+1++4260304623843:EN'

The LIN segment represents a line item position in a dispatch advice. Thereby, 1 is the line item number assigned by the sender.

The following number 4260304623843 represents the item number. The third part EN indicates the type of number – in this case a GTIN (global trade item number) was used.

QTY segment

QTY+12:110:PCE'

The quantity segment is used for the definition of shipping quantities.

The first part of the composite data element indicates the type of quantity.

12 = Despatch quantity

21 = Ordered quantity

59 = Numbers of consumer units in the traded unit

The second part is used to provide the actual quantity – in this case 110.

The third part indicates the unit of measure in which the quantity is provided. Possible values are for instance:

PCE = Piece

KGM = Kilogram

PND = Pound

RFF segment

RFF+ON:8493848394:1'

The RFF segment is used to provide reference numbers.

ON indicates a reference to an order message. 8493848394 is the referenced order number and 1 is the position number in the referenced order message.

CNT segment

CNT+2:3'

The CNT segment is used to specify control values that can be used to check the integrity of the message upon receipt.

In the example above 2 indicates, that the following value represents the number of line items in the message. The control value 3 for the number of line items is correct, since the message actually contains three line item element.

UNT segment

UNT+34+1'

The UNT segment represents the message trailer.

The first number 34 indicates the number of segments in the message from the UNH to the UNT segment and is thus also a check digit. The number 1 must be the same message number as used in the UNH segment. This also serves to check the integrity of the EDI message.

UNZ segment

UNZ+1+MSGNR4711'

The UNZ segment represents the interchange trailer and is the last segment in an EDI interchange.

The first number 1 represents the number of messages contained in the interchange. The second entry MSGNR4711 is the same interchange number as in the UNB segment and also serves to check the integrity of the message.

Summary

Although incomprehensible at first glance, a closer look at an EDIFACT message shows the information hidden inside. In contrast to markup-based approaches such as XML, the size of an EDIFACT message is very small, since only coded information is transmitted and no space-intensive markup is used.

Although one might think that space does not matter with the storage capacities and Internet bandwidths available today, EDI message size is of major relevance. For example, Deutsche Telekom still calculates X.400 traffic on a kilobyte basis.

EDIFACT and its subsets are the most widely used EDI data exchange formats of companies worldwide. As a supplier to large companies or as a buyer of large companies, one therefore often has no choice but to use EDIFACT.

Questions?

Do you have any more questions about EDIFACT? Please do contact us or use our chat — we’re more than happy to help!

Der Beitrag EDI Standards Overview – Structure of an EDIFACT File erschien zuerst auf ecosio.

]]>